Romania’s law enforcement agencies are failing to tackle disturbing online violations and stop parents, including mothers, sexually exploiting children for financial gain.

Warning! This story contains details of abuse that readers might find upsetting

Romanians are proud to have one of the world’s fastest, most reliable internet networks, but rarely have a good word to say about their creaking justice system.

The combination of these two elements has allowed dark elements of the virtual world to flourish. The sexual abuse of children online is one of them.

This is a topic few will talk about, as BIRN found out in an investigation focused on one of its least conscionable forms: mothers mistreating their own children for paying clients watching from abroad.

The numbers of such cases are small, but were sufficient to surprise even child protection experts contacted for this article. Romanians seem largely unaware that any such abuse is going on at all. Silence nurtures a damaging culture of ignorance, and one of the EU’s poorest countries is failing to protect such children.

Child abuse for profit is of course not only Romania’s problem. Authorities worldwide are struggling to combat it, with criminals often seeming one step ahead. Online encryption – hailed by privacy advocates, feared by governments but now the global norm – is their latest weapon.

But in Romania, even when abuse of minors is discovered, law enforcement is ill equipped to deal with it, legal experts say. Poor funding, slow investigations, unfilled prosecutor posts, and little guidance for judges all mean that punishments can vary wildly and are often lenient by international standards.

Alerted first by a US news report mentioning Romanian abusers, BIRN analysed little-publicised official data about child sexual abuse material (CSAM) – a term which the European police organisation Europol prefers to “pornography” to underline that minors can never be deemed to have consented.

In Romania, BIRN found an increase in the number of children sexually abused by their own parents for financial gain – with many victims left afterwards living under the same roof as their abusers, which child experts saw as the most damaging state failure of all.

From a couple of known cases annually 15 years ago, this grew to an average of around 50 a year in 2022-24, Romanian prosecutors say.

Usually it is the father inflicting the abuse. But more unexpected, perhaps, is that a number of mothers have abused their own children, mostly when they are too young to go to kindergarten.

From court cases and prosecutors’ press releases, BIRN counted over 100 documented cases involving infants since 2009 in Romania.

ELENA AND HER NEWBORN

It is often foreign agencies that shed light on what is going on in Romania. When the US FBI’s Violent Crimes Against Children Section began in 2015 to investigate a group of 20 men, all later convicted, it uncovered a group of Romanian mothers, many known to each other and some related, who had been raping their own newborns and toddlers for money.

One who played a big role was Elena. BIRN has not used full names of those involved to protect the identity of children.

Born in 1991, she married soon after high school and from around the age of 18 tried to earn quick cash doing sex shows with her husband in video chatrooms at a studio they hired. But the money wasn’t great and the competition fierce.

Elena bought a computer to launch her own solo shows from home, first in Bucharest and later in Vărăști, a village the family moved to outside the capital. In spring 2013, the young mother became pregnant a second time. Rather than curtailing her career, this gave it a boost as she found a lucrative market of men keen to watch pregnant women engaged in solo sexual activity.

Elena’s chatroom provider began closing in on abusive content so she switched onto Microsoft’s Skype. Men from the US, Canada, Belgium and the Netherlands told her they would pay handsomely to see her and the child together once it was born, and Elena agreed. Her daughter was only four months old when the abuse began. Her main customers were a 40-year-old cook from South Carolina, and a 58-year-old from Dallas, Texas. Both spent tens of thousands of dollars to watch her and other Romanian mothers abuse their own babies and toddlers.

In October 2015, with FBI at his door, the cook threw his 500 GB hard drive into the toilet but failed to destroy its incriminating evidence, according to Bureau statements. His recordings of their sessions helped secure his 40-year jail term in 2018 for participating in an international child pornography ring. Elena was arrested in January 2016 and convicted of rape, child pornography and trafficking in minors (under 18s), a charge covering forcing them into prostitution or other forms of sexual exploitation.

Elena abused her daughter live on Skype for a year and a half, earning up to $100 a time for sessions of up to 16 minutes. In her bedroom, with Jesus looking down from a poster of the Holy Land on one wall and a brown teddy bear on a cabinet, she raped and abused her baby daughter as foreign clients watched, court documents stated.

Under Romanian law, rape includes any form of sexual penetration and since 2024 it has also included any kind of sexual abuse of someone under 16, if the perpetrator is at least five years older.

At her Bucharest trial, Elena blamed her clients, and also said her husband had forced her to work as a prostitute and to exploit their daughter for money, something he denied and was not prosecuted for.

Elena was sentenced to just over six years in prison – reduced from nine years after she provided information about her clients. She was stripped of her parental rights, meaning that authorities would be involved in all future decisions about her children. Usually this means the child is taken into care, but sometimes visits are allowed.

She was released in 2020. Soon after, local media said her husband had taken her and the children back. The local child protection agency told BIRN the family had moved away and they had lost track of them. Authorities in her new area may not know about the family’s history, and it appears fairly easy to slip between the cracks and evade parental restrictions.

MATERNAL SEX ABUSE: A TABOO

Child protection experts say Romanian society is largely silent about sexual abuse of minors. “We live in a culture of blaming the victims and shame. We want to keep the abuses secret,” said Mihaela Dinu, a psychologist at Save the Children Romania.

Andrei Marinescu runs an anonymous child sexual abuse material reporting hotline for the same charity. He says it is a vital service since many people are reluctant to report abuse formally and unwilling to testify in court. He called for awareness campaigns to bring the issue out into the open in a society that would rather not know.

“Sexual abuse, which comprises physical and emotional harm, is a taboo within families,” he said. Most abusers are men and many people appear unaware of the smaller but disturbing amount of abuse by women, especially of their own children. The unacceptability of such behaviour is exactly what gives some clients their kicks.

“I like shows with kids since it is a taboo,” Justin McKinley of Florida told US investigators, court documents show. He spent around $40,000 in a year (2014-15) for watching child abuse on Skype, saying Romania was a prime source because of its good internet.

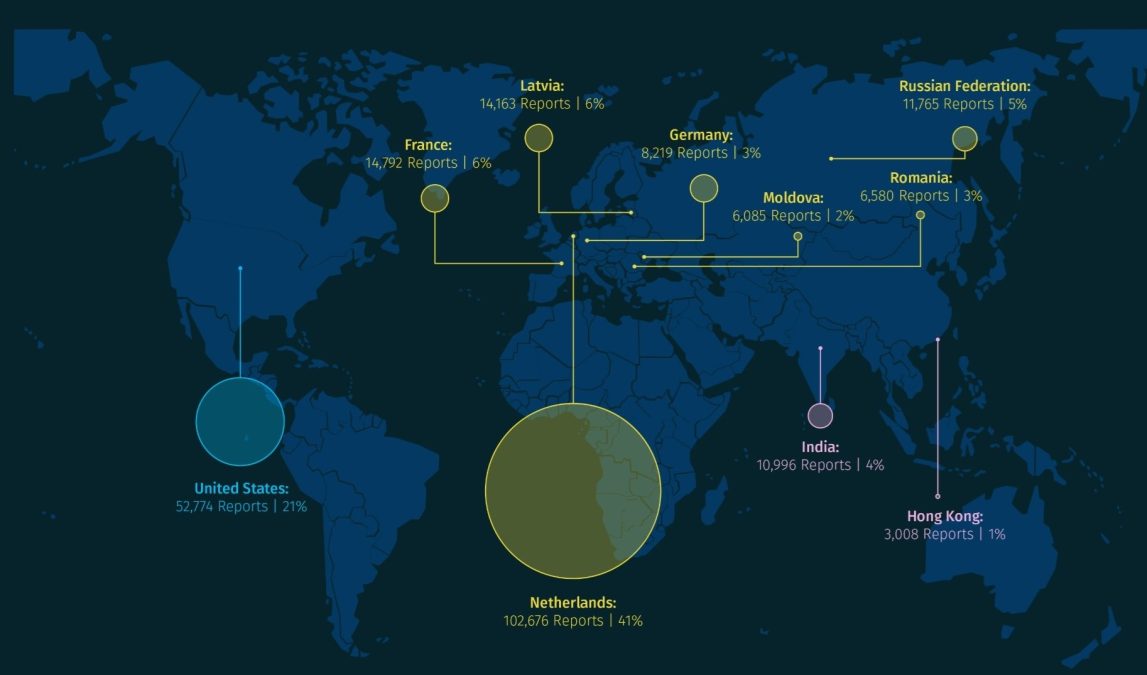

Romania often ranks in the top ten worldwide for internet speed and connectivity, beating many more developed countries. But it is also in the world top ten for hosting child sexual abuse material.

At least three women in Romania raped their toddlers for McKinley: Elena, Lucia, and her sister-in-law Natalia, both of Bucharest. Lucia abused her daughter from the age of one month. When the girl was two years old, her father joined in to perform at least 129 sex shows, for which the couple received around $20,000. When Elena was arrested, Lucia called her clients to tell them to destroy any incriminating evidence, so the number of abuse sessions could be higher. Natalia earned over $50,000 in 2014-15 – a very high income in Romania.

A 2022 report from the US University of Massachusetts Amherst said few studies have focused on women sex offenders, but highlighted that such offenders “are more likely to abuse their own children or children they care for”.

The younger the victim, the harder it can be to detect abuse. Once children are at school, teachers and other outsiders are more likely to spot any problems.

Some convicted mothers such as Elena tried to use the young age of their victims in their defence, saying they would be too tiny to recall what had been done to them.

Gabriel Balaci, PhD, a psychologist at Vasile Goldiș University in the city of Arad who has also worked with paedophiles and abused children as a psychotherapist, said that for such women, the child is just an object, and they don’t see that what they did was abuse.

“Their maternal instinct is atrophied, and they feel a sense of seduction towards their clients. Receiving money validates their behaviour and they brag to their neighbours about their wealth, while keeping quiet about how they made it,” he said.

“Everything was a game,” Elena told during her trial. “I never felt sexually aroused. The only purpose was earning good money.”

TOO LENIENT TO ABUSERS?

Romania has limited public resources, weak rule of law, an ineffective judiciary and scant social protection for minors.

Laura Ștefan, an expert in justice reform, told BIRN the courts faced significant challenges dealing with sexual offences against minors. A lack of sentencing guidelines – a common aid to judges in other countries – meant punishments varied from judge to judge, with many showing leniency toward offenders out of line with international norms. Florentina’s case highlights the issue.

In early 2019, the newly married mother from Brăila, eastern Romania, filmed herself sexually abusing her son, who was only three months old when she began.

She agreed to send the materials to a man claiming to be a well-known Romanian comedian who had been grooming her, and who she hoped would help her into a show business career. The situation turned sour, and in a bizarre twist the man reported her to the Child Protection Agency.

The impostor admitted his role – but said he had done nothing wrong – and was jailed for seven and a half years. He said the woman who had actually committed the abuse was the guilty one who should be punished.

Florentina received a three-year suspended sentence and 60 days of community service for child pornography and rape, and her child was taken into care.

“It’s hard for me to understand a suspended sentence in such a case,” Ștefan said. “We are shockingly lenient and understanding toward offenders.”

In 2024, the EU recommended minimum sentences for a range of abuses, from one year for making a child watch sexual acts, to at least ten years for the most serious offences.

Florentina’s son was later placed with his grandparents, with whom he was still living as of 2024. The court did not strip her of parental rights, so she can still visit him under supervision.

Romania’s justice system is underdeveloped and three out of ten prosecutors’ posts go unfilled. It still lacks prosecutors and judges trained to deal with sexual offences. The courts are known for inconsistent verdicts, inefficiency and trials that can last up to a decade.

Efforts are being made to improve, but they are slow. In 2018 Romania announced the first specialised prosecutor roles to combat crimes against or by minors, but took another four years to follow this up with a guide on investigating child sexual abuse.

An official report says four fifths of the over 18,000 child sexual abuse cases reported between 2014 and mid-2020 went unprosecuted.

In 2022 the Judicial Inspectorate, part of the Superior Council of Magistracy which guarantees judicial independence, said training for prosecutors and judges on child abuse was still inadequate.

In 2019 the EU’s executive arm, the European Commission, told several member states they were not complying with existing rules on combating child sex abuse, including special measures to fight online abuse. Whilst other notified countries like Sweden, France and Germany complied swiftly, Romania was served with a second warning in 2023. In March 2025 the Commission told BIRN that Bucharest was now complying, but gave no details as to what had been improved.

In 2022 the Judicial Inspectorate, part of the Superior Council of Magistracy which guarantees judicial independence, said training for prosecutors and judges on child abuse was still inadequate.

In 2019 the EU’s executive arm, the European Commission, told several member states they were not complying with existing rules on combating child sex abuse, including special measures to fight online abuse. Whilst other notified countries like Sweden, France and Germany complied swiftly, Romania was served with a second warning in 2023. In March 2025 the Commission told BIRN that Bucharest was now complying, but gave no details as to what had been improved.

KEEPING VICTIMS AWAY FROM ABUSERS

Legal expert Ștefan said that one of Romania’s biggest problems was vulnerable children remaining in, or being returned to, the homes where they were abused.

“We tend to simplify things and most people say the best place for a child is at home. But if the mother and father are the ones abusing the child, is it still good for them to be at home?” she said.

“The most crucial aspect is ensuring that children are placed in safe environments and not left with their abusers. What kind of life will that child have?”

Data collected by the National Authority for the Protection of Child’s Rights and Adoption (ANPDCA) revealed that nearly half of known child sex abuse cases in recent years occurred within the family, with nine out of ten victims being girls. Eighty-five percent of children abused by a relative stayed with their family. Despite this, it had no data about the number of known abusive parents or how many faced any restrictions on their parental control of their children.

”Romania is still learning about child protection,” Ștefan said. “We see here all the cracks in public services.”

Florina lived in a village 75 km northeast of Bucharest. A mother at 21, she began abusing her baby boy in 2014 when he was just 25 days old. He was raped almost daily, and sometimes twice a day, for a year for paying online clients, and her trial revealed particularly shocking, sadistic sexual abuse.

Despite this, Child Protection Agency psychologists only evaluated the child four years later, and said he was emotionally stable, though impulsive, anxious and insecure.

Dinu, the Save the Children psychologist, said effects of abuse often took years to show up. One victim she worked with was four when abused but was admitted to hospital a decade later with resultant severe depression.

Contrary to the mothers’ stated hopes that their children would be too young to suffer, experts said that the smaller the victim, the more chance there was of long-term problems, such as anxiety, depression and thoughts of suicide.

“The younger the child is when the abuse occurs, the more devastating the consequences,” said Balaci, the psychologist from Arad. “This trauma shapes the child’s entire life, underscoring the need for long-term monitoring.”

Florina was jailed in 2019 for six years and eight months and released early in 2024, on condition she stay away from her child for another year. After that she will legally be able to reunite with her son, who will be about 11. As with Elena’s case, authorities seem unable to check if the rules are being kept to. Florina’s family all moved away from the area.

STRUGGLE FOR INFORMATION

Getting a fuller picture of the extent of known child sexual abuse in Romania appears impossible. Though some information is in the public domain, much is not, and many officials were reluctant to speak.

BIRN contacted individuals mentioned in this report and others, via prison authorities or sometimes by visiting their homes but, unsurprisingly, neither they nor their relatives agreed to talk. Most messages went unanswered.

Less acceptable was the general lack of responsiveness from official bodies who often failed to reply to questions, declined to provide information or gave unhelpful vague responses. Romanian anti-child abuse police refused an interview request, as did the state prosecution department responsible for countering child sexual abuse material.

On the problem of uneven sentencing, courts declined to comment and the Superior Council of Magistracy was unable to outline any steps taken to harmonise judicial practices and implement recommended sentencing guidelines.

Child sexual abuse material, a worldwide problem, is now present on peer-to-peer file-sharing networks, popular messaging apps, gaming platforms and on the so-called dark web.

Romania has a serious problem. One internet watchdog report from 2019 put it in the top five EU countries for posting child sexual abuse material online and another from 2021 ranked it in the world top ten, behind the United States, India and several larger European countries, for hosting such material from anywhere.

Despite this, Romanian police have never asked to join the Virtual Global Taskforce of 15 national law enforcement agencies combating this crime. The police and interior ministry declined to comment.

Since 2021, this Taskforce has warned that end-to-end encryption (E2EE) of messaging is a major threat to its work. Live streaming of abuse hobbles efforts to combat it by leaving little in the way of evidence, since no files need to be downloaded (unless it is recorded).

Such encryption was introduced by Apple in 2014 and is now common practice for nearly all online communications platforms.

Britain’s National Crime Agency – which chairs the Virtual Global Taskforce and is more open to discussing the topic than Romanian police – said this meant online platforms could no longer detect child sexual abuse material and urged them to find a solution, which many experts think may mean relying massively on artificial intelligence.

“Privacy should not come at the expense of child safety, and it doesn’t have to. If the model does need to change, then so be it. All we ask is that the new model incorporates an alternative way that helps us continue to protect children,” spokesperson Hattie Hafenrichter told BIRN.

The European Commission sought new powers in 2022 to compel platforms to screen users’ messages for child sexual abuse material but controversy ensued, with civil liberties groups saying it could pave the way for mass surveillance.

“Any legislative act that proposed access to end-to-end encrypted content would undermine digital security and amount to generalised surveillance of private communications,” said Bogdan Manolea, head of ApTi, a Bucharest-based digital rights NGO.

Save the Children’s Marinescu said Big Tech had to, and could, find a solution. “The internet companies must filter the content. Why do they not do it?” he asked.

Most mothers whose cases were researched for this story used Skype, whose closure was announced in 2025 due to falling popularity. Its owner Microsoft in the US did not respond to BIRN’s questions about child protection.

In 2024 the EU implemented the Digital Services Act, obliging major online platforms to find a way to remove illegal and harmful content including child sexual abuse material. This could lead to a clash with the anti-regulation US President Donald Trump.

While the struggle to find a balance between online privacy and fighting crime of all sorts is a global issue, there is plenty Romania can do to address its own shortcomings with weak institutions and a reluctance to bring unpleasant problems into the open. Until it does so, children, the most vulnerable in its society, will continue to pay the price.

This story was produced as part of the Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence, supported by the ERSTE Foundation, in cooperation with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Editing by Richard Meares.