The European Union has finally taken action against the pernicious tool of strategic lawsuits or SLAPPs – but Romania’s politicians have a habit of dragging their feet when it comes to transposing European directives.

“I would have been financially ruined. The stress created by such processes is incredible. They force us to abandon our principles,” one of dozens of journalists in Romania who was dragged into lawsuits because he disturbed the image of some businessmen, told BIRN.

SLAPPs, Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, can ruin journalists financially and destroy them mentally. Perhaps the worst consequence is self-censorship. Often, actions are withdrawn by the plaintiff only after they have taken a psychological and financial toll on the journalist.

Weaponizing the law against journalists is not new but recently the issue became international. Maltese investigative reporter Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed in a car bomb, at the time of her death faced almost dozens of lawsuits in the US, UK and Europe.

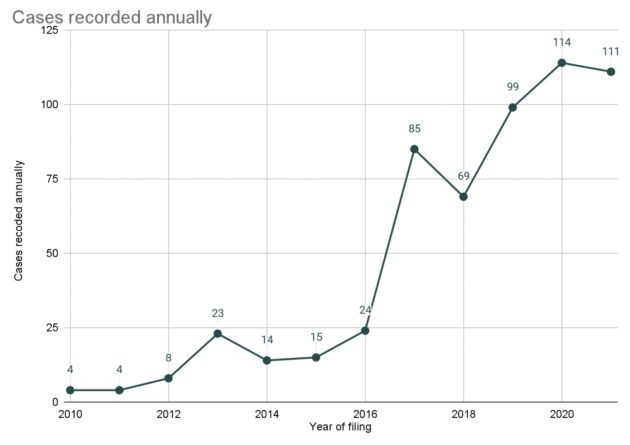

Her murder drew attention to the SLAPP issue. According to a 2022 report by CASE, the Coalition against SLAPPs in Europe, SLAPPs sky-rocketed in numbers in the last ten years.

Enter the ‘presidential order’

Revelations of dirty business in football brought great financial problems to the Romanian Center for Investigative Journalism, RCIJ, a well-known association of investigative journalists in Romania.

In December 2016, RCIJ began publishing articles on theblacksea.eu as part of the Football Leaks project, a large-scale cross-border investigation, based on the biggest data leak in the world of football.

Two Turkish businessmen, Arif Efendi and Arif Tevfik, as well as one of their firms, were among the main actors in the revelations. Two years after their names were mentioned in the articles, the two Arifs sued the RCIJ in several lawsuits.

Their first step was to obtain a “presidential order” to have their names removed from the site. This order is a special procedure in Romanian law by which a court can order a temporary measure in urgent cases. It must be enforced immediately.

The magistrate who issues the order does not judge the substance of the problem. The procedure is used mainly in family, property or enforcement disputes. For example, the judge can order temporary measures in relation to a divorce or building construction.

In contrast to the slowness of most trials in Romania, the presidential order is executed in just a few days; often, the person against whom it is directed is not even informed about the measure.

More and more businessmen or politicians are using this procedure because the fee to get a presidential order issued is only 20 lei, about 4 euros; if the plaintiff requests money, the fee can reach up to 200 lei. In parallel, they open at least one lawsuit.

Two years after the articles appeared, when no urgency was justified, Arif Efendi and Arif Tavik and Doyen Sports obtained a presidential order to delete their names and photos from the Football Leaks articles.

The judge considered the Turkish businessmen private individuals without public functions or activities in Romania, so their names should not have been mentioned. The judge also decided that as the journalists did not show the source of their information, the data was obtained “in non-transparent ways”, thus seriously damaging the image and dignity of the complainants.

In January 2019, the RCIJ was obliged to withdraw the articles until the date of the final resolution of the trial, but did not do so because it had not been notified of the issue of the order.

A little earlier, in December 2018, on the same day as the request for the presidential order was submitted, the Romanian lawyers for the Turkish Arif family registered another file in which they requested the same things: removal of the names and the prohibition of future publication of some articles related to the plaintiffs. In February 2021 they lost the case but appealed. The next hearing was set for September 2022.

Other lawsuits have followed, in one of which the court ordered the RCIJ to pay 1,000 lei, about 200 euros, for each day it did not remove the name and photos from the website. Almost 73,000 euros were collected in this way, without penalty interest. BIRN asked the RCIJ president to explain how the association had handled this situation but he did not respond by the time of publication.

Malaysian Wei Seng (Paul) Phua whose name also appeared in Football Leaks was not as lucky as the Turkish businessmen. Vexed that his name had been associated with a Hong Kong triad, affecting his credibility and business, he also sued the RCIJ and the two foreign journalists who wrote the article.

His request for a presidential order, submitted in June 2019, was rejected, however, because the RCIJ had transferred theblacksea.eu to an offshore company in Cyprus and none of the authors were members of the association. Romanian judges ruled that Phua must seek justice in the Cypriot courts.

Phua is still fighting another lawsuit in Romania to have his named removed. In March 2022, the court rejected his request, but he may appeal.

For those who bring lawsuits, it’s win-win

One of the authors of the article on Phua explained the problems faced by journalists who become targets in the courts. First, he says, journalists are generally paid too poorly to afford a lawyer.

One solution to this is finding a lawyer to represent you pro bono, or seek financial help from organizations such as Media Defence, the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom or Reporters sans Frontieres, RSF.

However, there are only a limited number of pro bono attorneys, and these organizations offer limited amounts, so it will be increasingly difficult for journalists to find help, as the number of SLAPPs increases.

“People who have money to spend on lawsuits win regardless of their outcome. Either the journalist gives up and removes the article, or faces a process for months or years, which is exhausting and discourages him from doing further investigations,” he pointed out.

The lack of financial resources of Romanian journalists when it comes to representation in court was noted in a 2022 report by the Center for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom.

According to it, most journalists work in poor conditions with uncertain job and financial prospects. “It is not entirely clear whether the use of SLAPPs is increasing, or whether what is increasing is actually the attention paid to them,” the report said.

One problem it identified is a lack of serious, evidence-based parliamentary initiatives to address the challenges journalism is facing.

“Some politicians attack combative journalism that makes them uncomfortable and use SLAPPs as well. In 2021, in an extraordinarily prolific and persistent campaign, Daniel Băluță, mayor of Sector 4 of Bucharest, filed 20 lawsuits against Libertatea journalists and filed complaints with several other state institutions,” the report recalled.

At local press level, the situation is even worse because these journalists are also under pressure from their bosses and have to face conflicts of interest from the judiciary, politics and media owners.

One journalist BIRN spoke with, who asked to remain anonymous, said that in his case, a Social Democratic Party, SDP, parliamentarian, bothered by 60 articles, sued his editorial office and its journalists, among them the owner of the publication.

During several years of trials, there were numerous negotiations between the owner and the politician.

“The trial affected me both mentally and financially. The lawyers who defended us were drawn into the PSD sphere. Businessmen who buy advertising in the newspapers I coordinate were under political threat. I was isolated … as the publication was forced through the party’s money to stop working with me.”

EU strikes back with a directive

The use of SLAPPs is increasing in the European Union, and the European Parliament in two resolutions in 2020 and 2021 condemned the use of such actions to silence or intimidate investigative journalists.

Saying that journalists play an important role in a democracy and must be protected, the European Commission sent several recommendations to member states in April 2022 as part of a future anti-SLAPP directive.

Currently, none of the Member States has specific safeguards against such procedures, and no EU-level rules address SLAPPs either.

The upcoming directive, whose text is subject to public debate, was published in April 2022, and will require Member States to revise their legislation so that complainants cannot use SLAPP procedures against journalists.

According to the document, if a journalist is sued, he can request a quick dismissal of the action. In this case, the plaintiff must prove that the claim is not a SLAPP.

SLAPP plaintiffs often allege defamation, but also breach of privacy or data protection laws. But the Commission says the right to the protection of personal data is not an absolute right.

Article 85 of the GDPR provides for a balance between the right to the protection of personal data and the right to freedom of expression and information, including processing for journalistic purposes or for the purpose of academic, artistic or literary expression.

Damaged reputation not always proven

The Group of the centrist European People’s Party, EPP, the largest political bloc in the European Parliament, was one of the promoters of the anti-SLAPP directive and seeks to protect investigative journalists and press freedom in the EU, according to a 2018 statement.

But the EPP’s concerns about the press do not seem to have been shared by Romanian National-Liberal party member Ramona Mănescu, a former MEP for this group between 2007 and 2019 and later Romanian Foreign Minister for a short period.

This politician sued Rise Project, a Romanian non-profit organization of investigative journalists, claiming that she was the target of a series of articles related to suspicious real estate deals.

Although the series of articles had started being published years ago, Mănescu was vexed by the revelations only in July 2019, when she unsuccessfully requested a presidential order to remove the articles and ban the publication of others.

Mănescu claimed that the articles, republished by other media, were not of general interest, generated hundreds of malicious comments and damaged her reputation.

According to Romania’s Civil Code, in order to issue a presidential order, the plaintiff must provide credible evidence that her/his rights have been violated and that the damage done is difficult to repair.

Mănescu failed to do this. The judge also ruled that the articles were in the public interest and considered that a presidential order in this case would have restricted freedom of expression.

Also in July 2019, Mănescu requested the same things in another file and demanded 15,000 euros in moral damages. She argued that Rise Project should have censored the defamatory articles before they were published because they violated her right to privacy and her honour and reputation.

The former MEP won that case, but the court awarded her only 4,000 euros and, importantly, allowed the articles to remain on the Rise Project website.

The magistrate considered that the journalist started from truthful information, but later distorted reality through value judgments that could have misled the public. “Under these circumstances, the court notes that protecting freedom of expression cannot take precedence over the dignity, honour, reputation and image of the applicant,” it said.

Rise Project also lost the appeal, but the politician’s joy was short-lived. In June 2022, the Bucharest Court of Appeal overturned the two previous sentences and ruled in favour of the journalist and the association. The former MEP must now pay over 18,000 lei – about 3,600 euros – in legal expenses. The decision is final.

In the meantime, in April 2021, Mănescu unsuccessfully filed a new lawsuit against Rise Project. There is no record that she appealed the decision. BIRN asked one of the founders of Rise Project to comment on these trials but did not receive a response by time of publication.

System tends to oppose change

Romanian judges tend to accept presidential orders and give justice to plaintiffs who feel their honour has been damaged even when that was not clearly the case. This should change now, with the entry into force of the anti-SLAPP directive, when Romania will have to amend its legislation.

There is, however, a big impediment. Most Romanian politicians try to postpone as much as possible the transposition of EU directives into national legislation or change their meaning.

One example is related to integrity whistleblowers. The way in which this directive was transposed into Romanian legislation attracted criticism from civil society but also from the European Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Romania was at risk of entering the infringement procedure due to successive postponements of the whistleblower legislation, so the bill passed quickly through parliament, but with major changes compared to how it had been agreed with EU officials.

The system tendency is to oppose changes. There are also judges who publicly assume political affiliations, although this is prohibited, and have a great aversion to the media. For this reason, even if the EU imposes the directive, it could take some time before journalists are fully protected from such SLAPPs.